The Science of Sharing Science

There is a lot of science out there that is not shared. Either because it is lost and forgotten, not understood, or intentionally kept secret. The gap between science and the layman’s general knowledge is also evident. There are gaps in what research has already done, what experts know, and what the public knows. The ownership of who owns and controls science has also been debated, and therefore, who is to know and what they are to know about science, is also in question.

People are sometimes afraid of science, choosing to remain ignorant rather than embrace the findings of scary diseases and disasters and change their destructive habits. Embracing new knowledge means having to tweak behaviours and move out of comfort zones. Science is also scary because of the other unknowns that one known digs up. We find out one thing, only to find the other 500 things we don’t know.

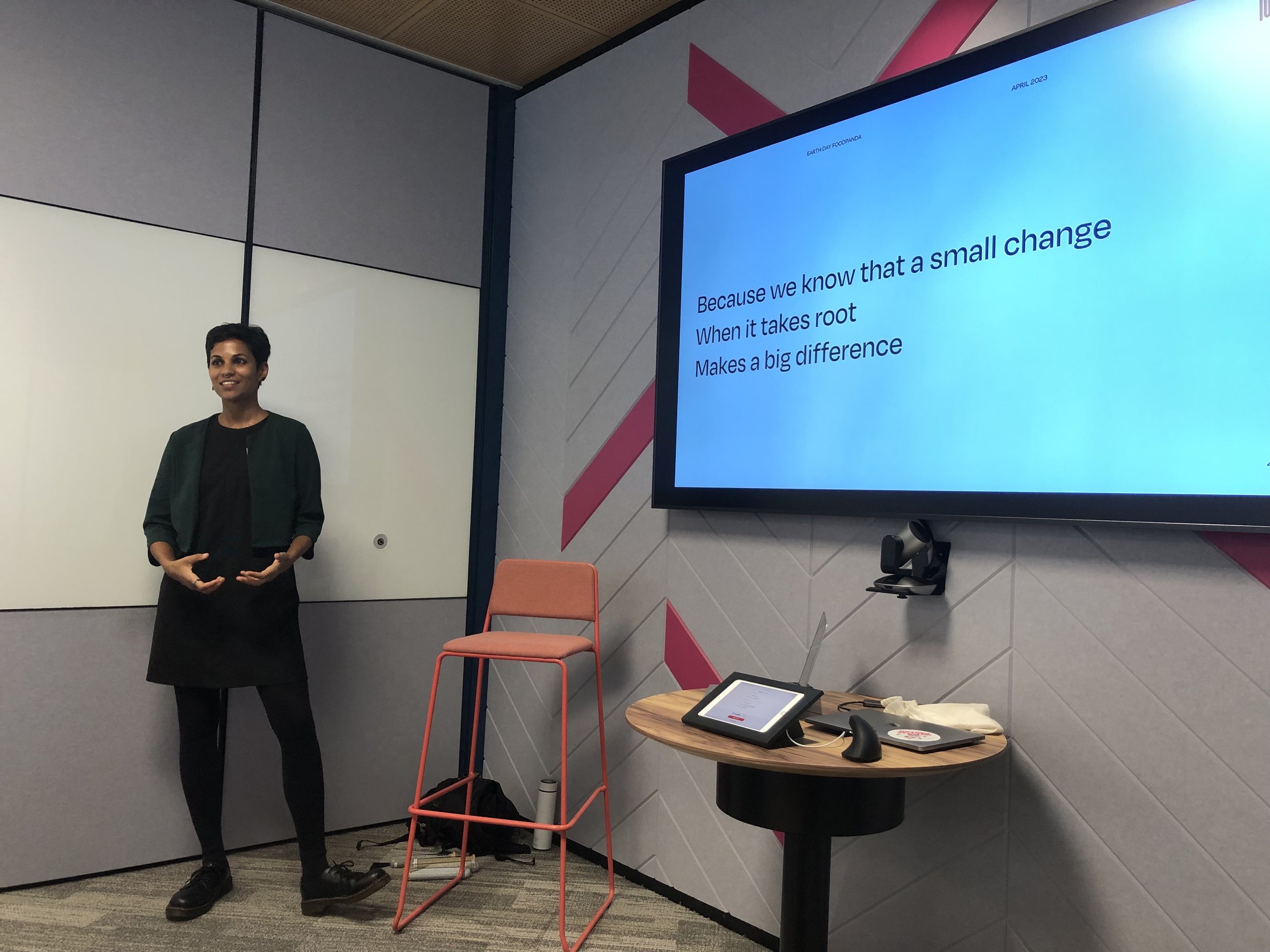

Packaging scientific knowledge into comprehensible, digestible and non-terrifying bite-sized pieces is difficult, and that’s why the role of science communicators is so important. Over the past few years, I’ve had small writing gigs, with companies such as AsianScientist, STEMMates, NurtureCraft and now, World Scientific Publishing. I am hoping to join the ranks of professional science communicators all over the world to bridge the gap by simplifying scientific articles for public consumption, and even for children.

If science isn’t communicated properly, people steer clear of it and continue to do things the scientific community already knows is detrimental for everyone. People also tend to read a mish mash of scientific information, not understand it and then become anxious. But knowing that they can’t do anything significant to change the situation, they eventually turn a blind eye. Ignorance is bliss.

This is what’s been happening with climate change. Climate anxiety and climate fatigue has been growing rampant. Many people are exhausted with the gloom and doom narratives, and therefore find it easier to say, “Someone else will rectify it” or “It is not mine to fix”.

It is easier to blame the developed countries for industrialisation, or to tell the developing countries to stop their attempts at modernisation. It is easy to expect life to go on ‘business as usual’. But we’ve already passed the tipping point, and are nowhere near the 2030 goals.

How can we convince people to change, when they don’t see a reason why? When they do not understand the science? When science is not communicated in a way they can understand? People do not protect what they do not love. They do not love what they do not understand, and they do not understand what they do not know. Therefore, we, who have the ability to teach and to communicate science, must.

Climate Freskers have been doing just that. Climate Fresk was created in 2015 by Cedric Ringenbach. Using picture cards relating to climate change, participants are able to put together a climate mural or “fresk” (fresco), and see the different causes, mechanisms and impacts relating to climate change in just 3 hours. All information for the session is sourced from The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change, which provides relevant and researched evidence to participants. Climate Fresk communicates complex information through the shared understanding of the participants and a trusty facilitator. The facilitator’s job is not to teach, just to ask guiding questions, clarify doubts and rephrase science into everyday speak. For example, to explain thawing permafrost by comparing it to a frozen pizza. The pizza is fine while it is frozen but if it thaws and remains thawed for a few days, out in the open, it starts to decompose – releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Much like permafrost thawing due to rising temperatures, releases carbon dioxide and diseases from decomposed, previously frozen animals, and bacteria into the atmosphere. Explaining the difference between melting sea ice and melting glaciers is another example. The first is already in the water, so even if the temperature rises and it melts, the water level is kept constant. Much like ice already in your drink. Whereas the melting glaciers, which were not previously in the water, now add to the volume, making sea levels rise. Like when you put ice in a filled cup – it overflows.

To date, more than a million people have attended the Climate Fresk sessions internationally, and in Singapore, 600 people attended in September alone. We need workshops like this to go viral. Everyone, everywhere has to have exposure to what is going on with our planet. It is not tenable to allow ignorance to continue anymore.

Not explaining science well is a barrier to change, and language is sometimes another. I started teaching English after spending time in South America. Trying to share information about conserving animals, baseline surveys, and scientific journals was insanely difficult because the people we were sharing with had no exposure to the language this information was written in. Marginalised communities are the ones who will be the most affected by climate change, yet, they do not have enough information printed, explained or taught to them in their language.

There is also this idea of colonialism in environmentalism. When I was volunteering in Bolivia, the locals thought all the volunteers were rich, that’s why we could come and work for free. NGOs camps are thought to be places that rich Westerners came to make themselves feel good, and take home happy stories and social media pictures. Colonialism is also exacerbating climate change by removing the indigenous caretakers away from the land. The displacement of indigenous people in Australia for example, are causing uncontrollable forest fires. The replacement of traditional ways of taking care of the planet with modern ones, may prove detrimental. So, if the colonials kick us out of our homes, and the colonials speak English, then, why should I read anything they write in their language?

How then do we make sure that science is communicated in a way that it is accepted, integrated, and acted upon? We have to make sure that we make it relatable. Aristotle’s rhetoric comes to mind here. We need to appeal to pathos, ethos and logos. People need to know that this is going to affect them – tug on their heartstrings – emotion, pathos.Then think about, why should anyone listen? If you are not busy building a name for yourself, you have no credibility. Be seen, go everywhere, keep talking, keep writing, keep at it. People will soon realise you must know something, if they keep seeing your name everywhere. Build your reputation – ethos – ethics. Lastly, evidence must be given. You have to show fact and make sure that whatever you are saying, is backed by quantitative or qualitative research – logic – logos. If people see that there is reason behind what you’re talking about – why they need to do these things, and that reason is based out of necessity – if you don’t do this, we’re going to slowly cook with 2°C increase in temperature globally. If you break down their actions into small bite-sized solutions and processes and let these build up into bigger tasks… Well, they might listen. And if you’re really good, you might make people act.

The bottom line is, science is complex. But if we don’t speak up and explain science, keep it to ourselves, lament about it, slowly the world will implode – and it will be our fault.